Supported by the SPI, Armin Sigmund joined the Belgian Antarctic Research Expedition organized by the International Polar Foundation (IPF). He spent 19 days at Princess Elisabeth Antarctica (PEA) Station to measure the surface mass balance and associated processes such as snow sublimation (transfer into water vapor) and snow transport by the wind.

The beginning of the project

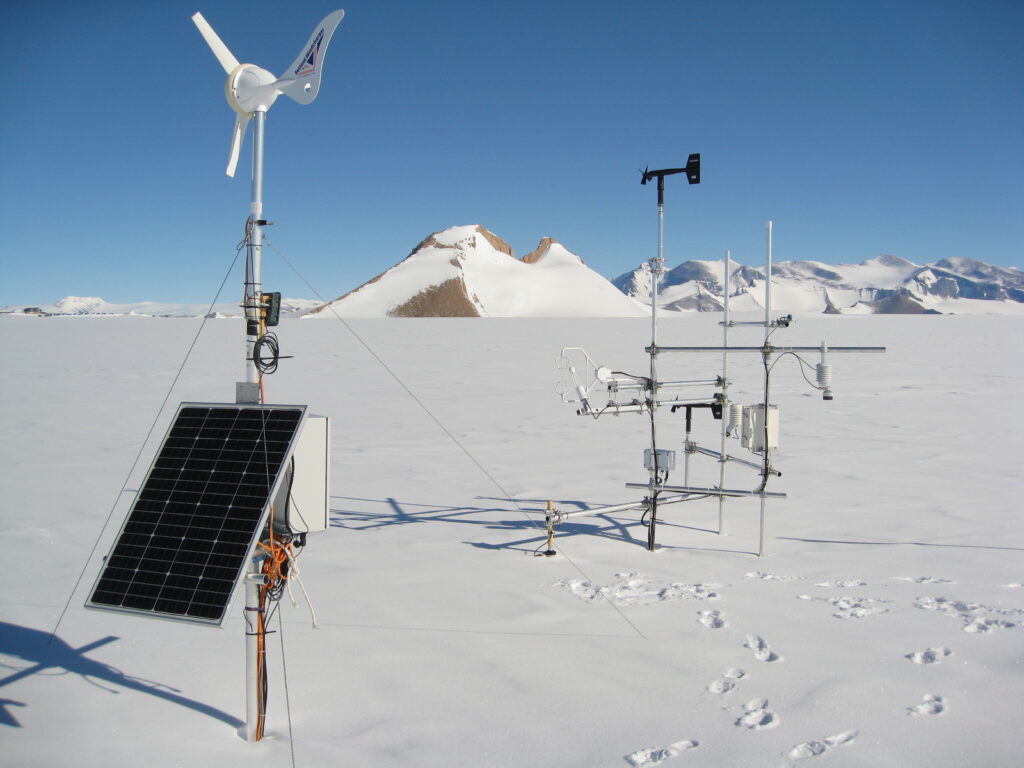

My first trip to Antarctica was part of a multi-year project, which started in the austral summer season of 2016/2017. At that time, colleagues of mine set out and installed two automatic measurement stations in the midst of the vast white landscape near PEA Station. The goal was to measure year-round data related to weather and snow.

As maintenance is only possible once a year, continuous measurements without data gaps are very challenging. Since the first expedition, each field trip has provided us with new lessons and a year later, one of our team members returned to Antarctica with new ideas for improvements and additional measurements. Two months ago, I had the chance to travel to this remote continent where incredible amounts of snow and ice dominate the landscape and some mountains create an impressive scenery.

Both of our measurement stations had been powered independently using wind and solar energy. A key problem observed in the previous year was the insufficient power supply during austral winter when it remains dark all day long and the system is only powered by the wind generator. After operating for a few years in the cold and windy environment of Antarctica, the wind generator appeared to be less efficient. Therefore, part of my mission was to guarantee a more reliable power supply.

At the first arrival in the field, I was excited to see how much data had accumulated on the memory cards and how much snow had accumulated at the site throughout the year. Wow! The snow surface was about half a meter higher than a year before! The snow particle counter was completely buried in the snow although it should measure snow transport in the near-surface atmosphere.

A new measurement site and new sensors

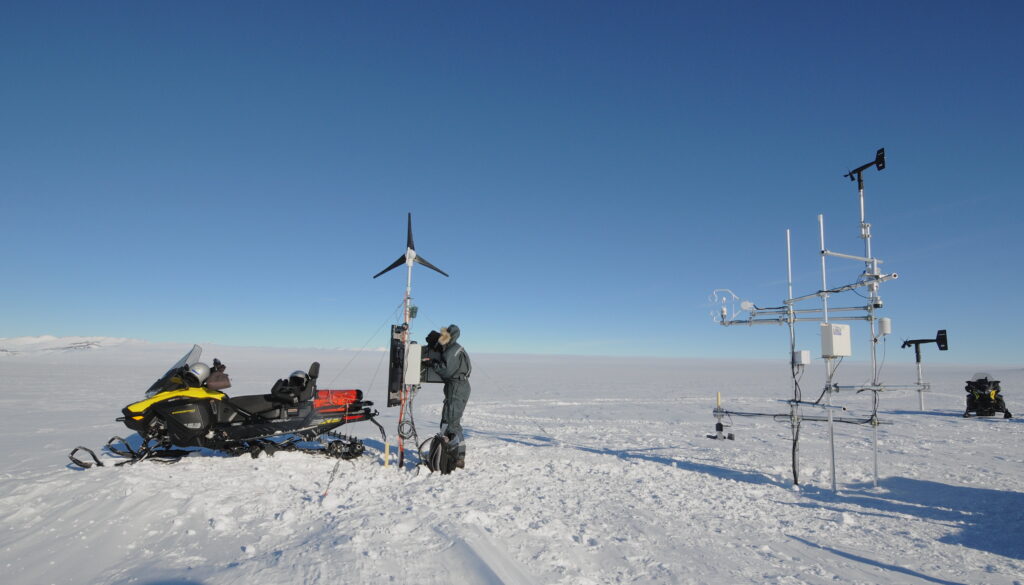

As suspected, the data on the memory card did not cover the whole year because of the power problem during the austral winter. Therefore, we moved the measurement construction to the direct proximity of PEA and powered it using the base station’s electricity. Thanks to the great help from other participants of the expedition, especially from our field guide and doctor Martin Leitl, we admired the construction at its new location after two afternoons’ work. Later, we added additional instruments such as two radiation sensors to study the effect of blowing snow on the radiation balance.

Extreme conditions at the second site

Our second measurement station is situated at the edge of the Antarctic plateau, a colder and windier place, 40 km away from PEA. After retrieving the data from that station, I was curious and checked it for the lowest air temperature. In austral winter, it frequently drops to -40 °C! And it can feel even colder due to strong and persistent katabatic winds coming from the interior of the ice sheet. Luckily, I was there in austral summer with temperatures around -17 °C.

Collecting complementary data

When the weather was nice and I had some time left, I let a mapping drone fly and take high-resolution aerial photographs of the snow surface. In combination with GPS measurements, we use this fascinating technique to determine changes in surface elevation between two drone flights. Also, I regularly took samples of the surface snow to get insights into the effect of sublimation and snowfall on the isotopic composition of the snow.

Work in progress

Although my field trip is over, the exciting work continues. The collected data will be useful for improving simulations of the surface mass balance of the entire Antarctic ice sheet. With this effort we hope to contribute towards improved predictions of sea level rise. I thank the SPI for supporting the project.

Armin Sigmund is a PhD student in the Laboratory of Cryospheric Sciences at EPFL, Lausanne. His field trip took place in November/December 2020 with financial support from a Polar Access Fund grant.

Header photograph: © 2020 Martin Leitl, all rights reserved

© 2021 Armin Sigmund, all rights reserved