Changes in climate affect the sliding of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets towards the oceans in several ways. One is that when surface meltwater accesses the bed of a glacier or ice sheet, it changes the speed at which the ice slides over its bed. The coupling between climate and ice sheet dynamics remains the greatest uncertainty in global sea level rise predictions for 2100. HI-SLIDE seeks to find out whether increasing surface melting in the lower accumulation zone of the Greenland ice sheet is changing ice sliding.

Observations from the margins of the South-West Greenland ice sheet – where melt is plentiful and ice is thinner – have previously revealed an overall decadal slowdown in ice sliding during a period of 50% more melting. This is in stark contrast to short timescales, when surface meltwater, which drains to the bed can transiently increase ice sliding.

There are feedbacks at play between the amount of water, which drains to the bed and increases water pressure, and the act of water flow, which carves drainage channels into the ice or bed, making space for the water and therefore reducing water pressure. Under certain conditions these feedbacks can lead to slower annual ice sliding. At lower elevations, we believe that this is caused by a more connected and efficient plumbing system that drains away more water stored at the bed. This acts to increase the contact between the ice and its bed, adding friction, slowing down sliding.

However, at higher elevations above ~1,500 m asl (above sea level), air temperatures are cooler so there is less melting, and ice is over a kilometre thick so it becomes very difficult for meltwater to drain to the bed. These are very different conditions to those at lower elevation. Our methods for observing ice motion from satellite images do not work well as the ice surface is very smooth. We therefore do not know whether ice sliding at these elevations has changed in recent decades.

So, to the work of HI-SLIDE: we are trying to find out whether there has been any change in high-elevation sliding during the last two decades. We are making field observations as this is the only way to reliably record annual ice motion in this area. Ultimately, HI-SLIDE will combine existing field observations of ice motion made during the 2000s with our new observations.

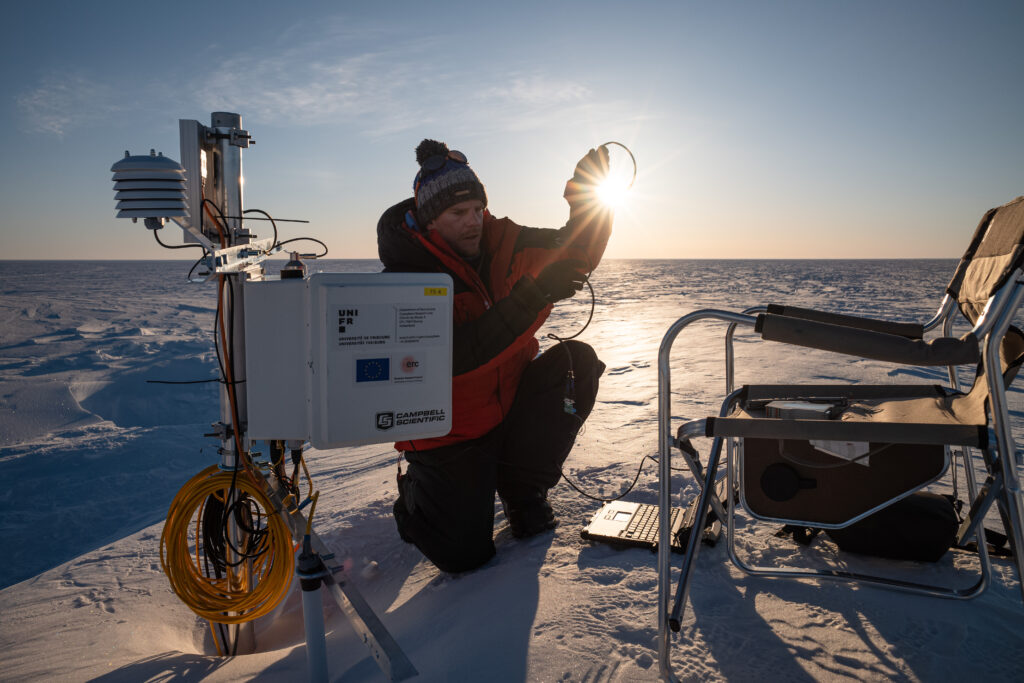

HI-SLIDE is tightly integrated with the European Research Council “CASSANDRA” project based at the University of Fribourg, which is investigating firn densification and the shifting runoff limit of the Greenland ice sheet. We are undertaking several seasons of fieldwork on the ice sheet. This spring, our team of four travelled to Greenland to drill firn cores, maintain monitoring equipment and, for HI-SLIDE, install a measurement network of five autonomous dual-frequency GPS stations on the ice sheet, located from 1,600 m asl to 2,000 m asl. Most of our stations are located at sites where ice motion was last measured around 10 to 20 years ago.

One cold evening in mid-April, we were flown onto the ice by two helicopters along with our two tonnes of equipment and left in the gathering dark to manage our first night sleeping in temperatures below -30°C. With our snowmobiles, we then travelled 90 km up the ice to install our main camp: a personal tent each, a mess tent and a workshop tent.

Over the following three weeks, we drilled seven firn cores, made measurements of winter snow accumulation, maintained instrumentation installed the summer before, and installed our new stations. By the time we left the ice sheet 24 days later, we had travelled some 1,200 km by snowmobile, visited 10 measurement sites, eaten at least 200 kg of food and watched the polar night gradually disappear. We had endured six days of storms, with blowing snow which continually threatened to bury our tents, making our shovels probably the most important tools of the field season. We also had two birthday celebrations – and zero showers.

This spring marked the end of a successful start to the HI-SLIDE project. We are now waiting for next spring, when we will head back to the ice to download each GPS station and get them ready for another year of measurements. Then it will finally be down to the most interesting business: has ice sliding in this area changed since it was last measured in the 2000s?

HI-SLIDE is funded by an SPI Exploratory Grant and is a partnership between the University of Fribourg and the University of Edinburgh. It is integrated with the European Research Council-funded project “CASSANDRA – Accelerating mass loss of Greenland: firn and the shifting runoff limit”.

Andrew Tedstone is a senior researcher at the University of Fribourg. His field trip took place in spring 2021 with financial support from a SPI Exploratory Grant.

Header photograph: © 2021 Andrew Tedstone, all rights reserved