Uf! It is 3 pm on 8 December, and we have finally finished setting up a weather station at 5366 metres above sea level on Cerro Tapado, in the dry Andes of northern Chile, after a kilometre-plus climb from the valley, and many weeks preparing sensors and logistics. I feel elated and exhausted at once.

It has not been completely easy getting to this point. We had planned to set up the station in November but the authorities closed the road. Then on 1 December we actually made it to the study site with all the equipment, but ran out of daylight and had to go down, leaving everything tied to rocks so as not to be blown away by the wind. Thankfully it was not!

We have come to measure sublimation — a process by which glaciers and snow lose mass to the atmosphere in the form of water vapour. It is rarely measured at these altitudes, yet it is an important outflow in the alpine water balance, especially in this very dry region, and can be a key uncertainty in glacier and hydrological models.

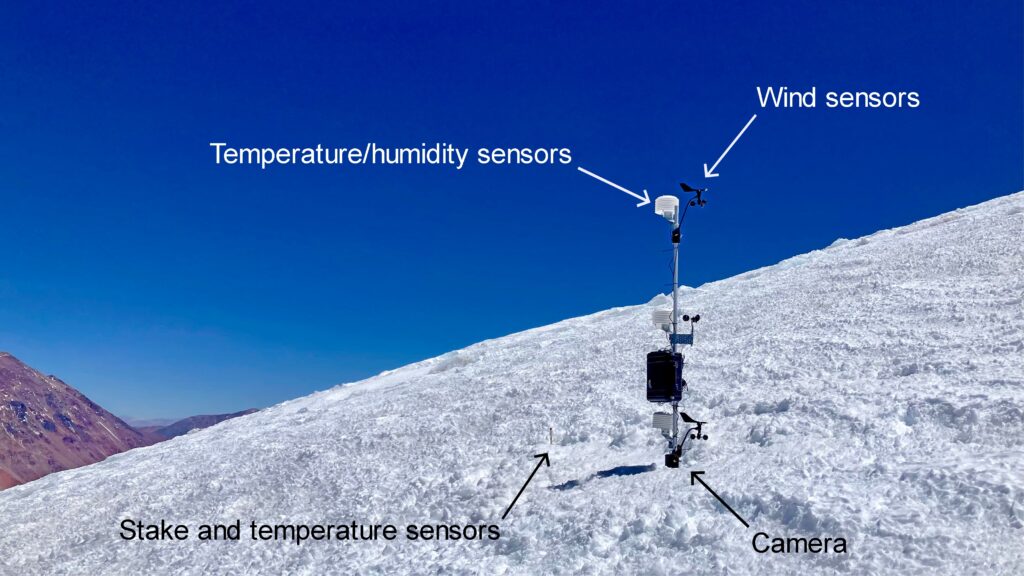

The equipment is simple. Humidity and wind speed sensors at different heights provide wind speed and vapour pressure gradients at the surface of the glacier, from which we can calculate sublimation. A stake drilled into the ice and viewed by a camera indicates the total loss or gain of ice and snow at that point. Temperature sensors in the ice tell us how close it is to melting. Importantly, all the sensors and batteries have to be able to withstand the very low temperatures and high winds they will experience in this extreme environment.

If all goes to plan, the station will take measurements throughout the summer, and provide valuable validation data for a modelling study of how the high-altitude part of the glacier is changing through time, and will continue to change into the future. In particular, we want to know how sublimation is changing, and how this will affect mass loss and runoff from the glacier more broadly.

I would like to say a big thank you to the Swiss Polar Institute for funding the project, via the Polar Access Fund; our collaborators CEAZA for their hospitality during my stay in Chile; and Álvaro, Jaime, Dan and Tom for all their hard work preparing equipment and hiking up the mountain with me at 3 am (twice, in Jaime’s case). Saludos!

Michael McCarthy is an early-career researcher at WSL. His field trip took place early December 2022 with financial support from a Polar Access Fund grant.

Header photograph: Drilling a hole for the weather station using an ice auger. © Daniel Thomas, all rights reserved.