The flight into Greenland leaves a strong impression. Everyone in the small red plane is leaning towards the windows to stare at the expanse of white below. For a moment you think it must be clouds stretching to the horizon, but then you see the small details, a mountain peak, a blue patch of water, the exposed rocks on the coast. Nothing really prepares you for a desert of frozen water that large.

The seemingly endless white splits into glaciers which our plane approaches through a series of fjords. The landing into Narsarsuaq is fun if you like amusement rides, and finishes rapidly at the end of a short runway. This region of the south coast hosts more vegetation than you might expect, with land even used for farming. The town we have flown into was developed into a US air base in the 1940s and is situated next to the fjord approximately 10 kilometres from the glacier, Kiattuut Sermiat.

The glacier has receded since the early Holocene, forming a glacial outwash plain in its wake. It is unknown if these environments act as sources or sinks of greenhouse gases in Greenland. Hence, the development of these environments has unknown impacts on climate, which is concerning given the increased warming of the Arctic from climatic feedback loops, known as Arctic amplification. We landed in Narsarsuaq to study the soil microbiome of these glacial outwash plains and understand the greenhouse gas interactions occurring across this landscape.

We stepped out of the airport with eight bags between my supervisor, Prof. Ianina Altshuler, and I. This consisted of our sampling equipment, gas analysers and cooler, with our personal belongings stuffed between measuring instruments.

For our fieldwork we rode each day on our rented bikes to the end of the road, our goal to reach sites along the glacial outwash plain. We hiked through a valley of low bushes, grasses and small streams until the sky opened up to a wide space overlooking a grassy plain surrounding a rocky glacial river system. The valley walls are bare rock, the kind you find everywhere in Greenland that have been scraped and carved by passing glaciers. And the valley floor becomes less and less vegetated as you approach the glacier, until there are only rounded rocks and loose sediment.

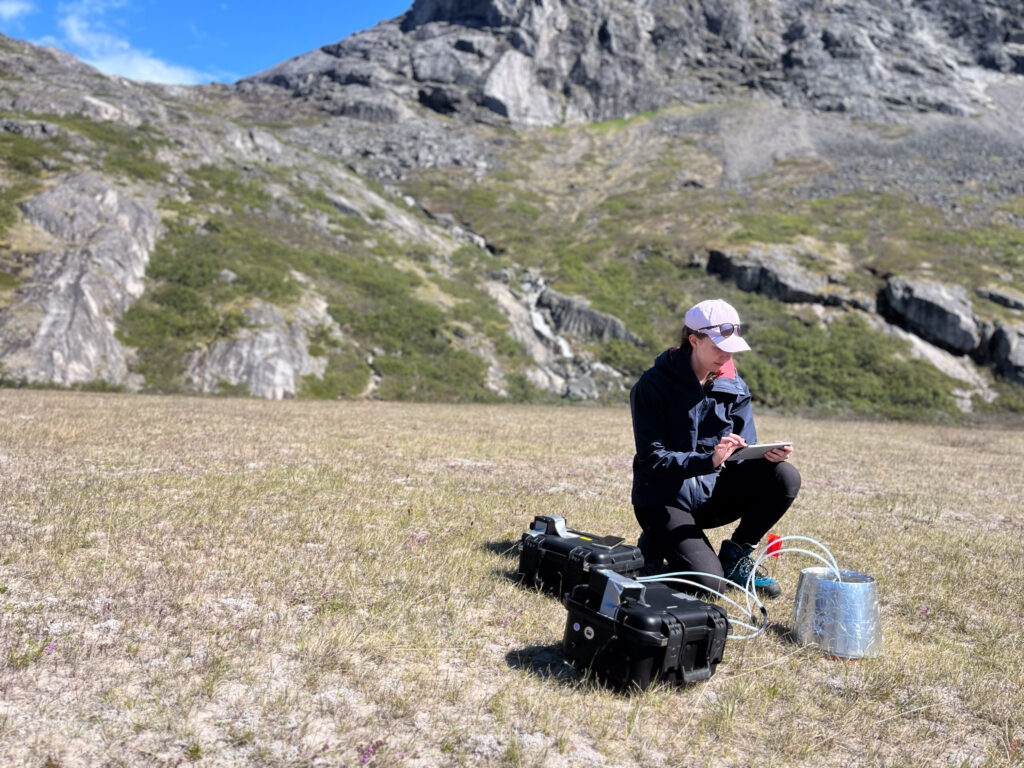

We set up the gas analysers for CH4, CO2 and N2O on preinstalled collars to measure soil gas flux, and with sterilised equipment we collected soil samples for genetic and physicochemical analysis. The gas measurements can take a long time and occasionally a few sheep passed by while we worked, sitting down in the sun to warm their woolly coats.

Everything was running perfectly until a week in. We woke up to great sunny weather and set out on our bikes with equipment for sampling and measuring a site midway along the outwash plain. By this point we are well practiced with our routine and were enjoying the crisp morning. But after warming up the instruments we quickly realised that the CO2 and N2O analyser cannot calibrate the correct gas concentrations.

To fix this we needed an ethernet cable, something we did not have in our emergency supplies of duct tape and spare parts. In our desperation we realised there must be a cable in the town somewhere, so we rode across Narsarsuaq in search of available cabled internet. Internet in Greenland is a valuable resource and as most people there are living in the modern era of Wi-Fi, our search was particularly challenging. After identifying two cables in the town, we managed to bribe our hostel manager with cake who lent us a semi-frayed ethernet cable. The cable pulled through and we were able to repair our analyser just in time for continuing our fieldwork.

Dangerous weather conditions and short runways make travel notoriously challenging in Greenland, particularly in Narsarsuaq. Most people spend longer than intended waiting for the pilots to land in high winds. We were delayed for a few days and had to stay in the only local hotel which provided a luxurious buffet lunch of traditional Greenlandic food, including seal, whale, muskox and fish. Before flying to the second site further north in Kangerlussuaq, we put this delay to good use and sampled the sites we missed when the analyser was broken.

The town itself is dusty but surrounded by enough vegetation to support muskox hunting year-round, as we learnt from a local who showed us his storage of muskox hides, salted for preservation. The glacial outwash plain connected to the nearby Russell Glacier consists of a winding glacial river and flood plains, similar to Narsarsuaq. Interestingly, both plains experience yearly flooding from glacial lake outburst floods, where proglacial lakes burst from their ice-dammed barriers and the water floods around and through the glacier in large quantities to the river system. However, the lake previously flooding through the Russell Glacier has recently started draining through a different outlet, altering the yearly floods in this region. With a local tour guide driving us along the dirt roads we sampled across this outwash plain which is over 20 kilometres in length.

A valley of green shrubbery surrounding bright blue lakes greeted us on the way to the Russell Glacier, until we abruptly confronted the wall of blue ice of the calving glacial front. But we were interested in the sediment and glacial flour lying in front of this impressive glacial mass and what implications this exposed sediment has for the climate in this vulnerable region. Our work continues now in the lab, with the frozen samples that arrived safely in Switzerland. We will pair the gas measurements of greenhouse gases in the field to our genetic analysis of the soil microbiome constituting these landscapes, to understand the implications of developing glacial outwash plains in Greenland.

Grace Marsh is a doctoral assistant at the Microbiome Adaptation to the Changing Environment Laboratory (MACE) at the EPFL Valais Wallis in Switzerland. Her field trip took place in summer 2024 with financial support from a Polar Access Fund.