Wide open skies, colourful flowers, and stillness all represent the Arctic tundra to me, but the tundra can also be harsh and unforgiving. Difficult logistics, the cold, and mosquitoes are just a few factors that can make botanical fieldwork a real challenge in the North, not to mention the tiny cold-adapted plants that can be so hard to identify and count – even when you’re not in a rush.

Throughout my academic career, I have spent many hours in the cold hovering over small patches of tundra trying to identify and count all individual plants found in an area the size of a small coffee table. I feel very lucky for all those opportunities, but climate change happens three times faster in the Arctic than anywhere else around the globe and for many areas in the north we only have very patchy botanical records – especially in the High Arctic.

Not knowing what different kinds of plants are found where makes it difficult for us to support conservation efforts, such as the establishment of protected areas, and it also makes it hard to study changes in the tundra ecosystem over time. What if there was a way of making the plant observations quicker and easier?

In summer 2023, I found myself in Cambridge Bay – a small community in Nunavut, Canada – attempting to answer this question. Together with my colleague Deb, I had travelled there from the University of Zurich, supported by an SPI Exploratory Grant, to see whether we could use “environmental DNA” (or eDNA) to help us speed up our botanical surveys.

I think of eDNA as the cool new kid on the block that could potentially make a big splash in the ecology world – but only once it has grown up a bit. Simply put, eDNA are small fragments of the plants’ genetic code found in the soil. Just like a police officer can identify a suspect from a hair left at a crime scene, we can use these small fragments to see what types of plants are found in an environment. At least, so goes the theory!

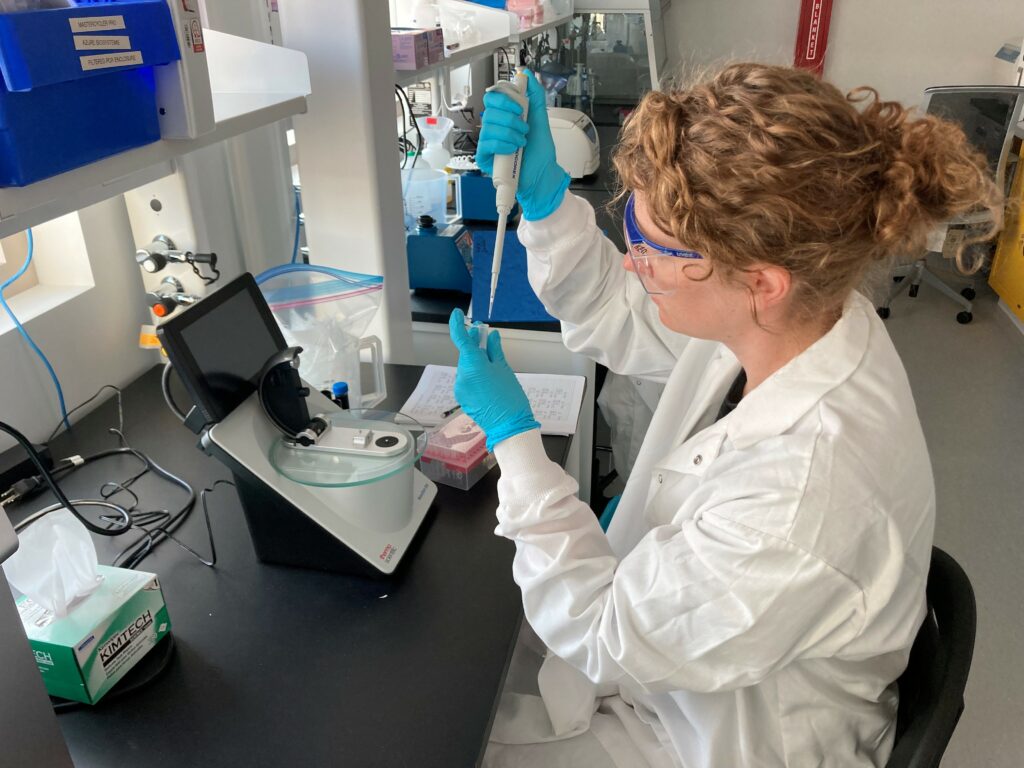

We were curious to find out whether the technology was ready to quickly scale up plant surveys across tundra landscapes. By chance, it just so happened that the Canadian High Arctic Research Station (CHARS) had recently opened up in Cambridge Bay – a modern research station with a specialised lab that would allow us to run most of the analytical steps required on site.

CHARS and Cambridge Bay became our home for six weeks during July and August 2023. From there, we would drive out every morning to our research sites, count plants, fly drones, or collect soil for the eDNA analysis. Like the locals, we were getting about in ATVs (or “quads” as you may know them) using the few gravel roads available.

The drive out in the morning was often my favourite – especially when we were going East to Ovayok – a large esker and territorial park. The tundra would put me in awe when the sun bounced off the many lakes and ponds. And I will also never forget the goslings that would hurry off the road when they heard us approaching on our noisy vehicle.

© Jakob Assmann, all rights reserved

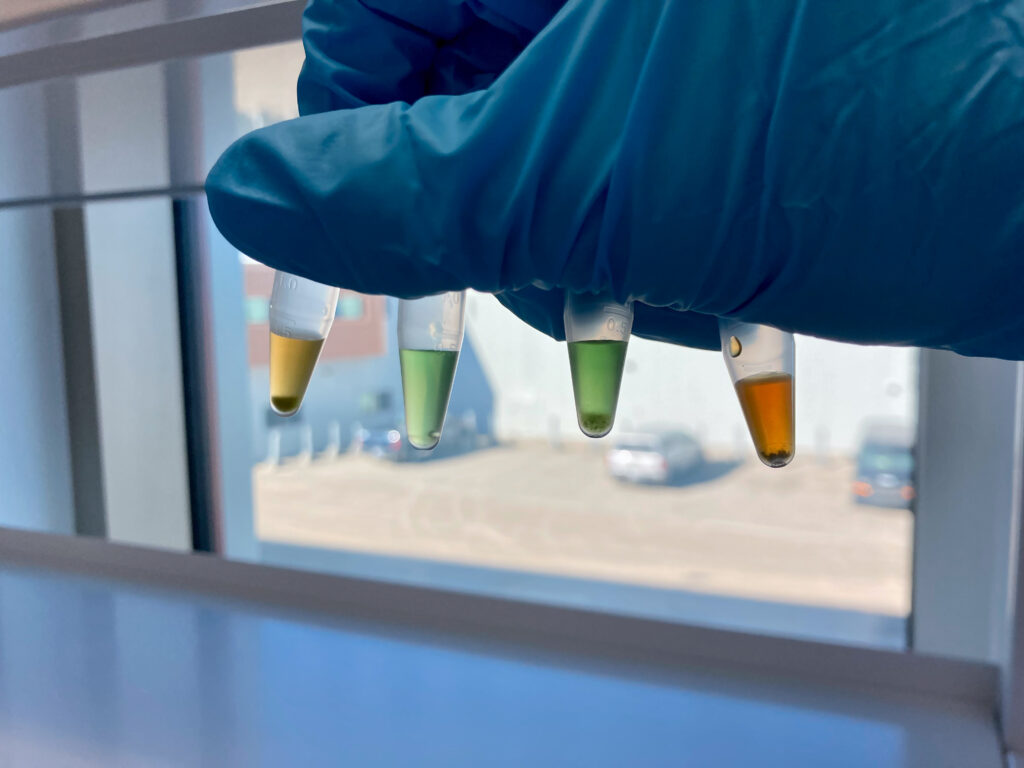

Towards the end of our stay, we spent more and more time indoors in the lab, post-processing the soil samples, identifying difficult plants under the microscope, and extracting DNA from the soil. One day, I was extracting DNA from some plant tissue samples that we had collected to generate a DNA reference library – when I was surprised by how much the colours of the extraction represented the character of each individual plant species. A bright green herb, a yellow sedge and a reddish-brown shrub all showed up in our small test tubes.

Conducting field work in Canada’s North is a real privilege. Travelling there from Switzerland is not only expensive in terms of money and carbon, it is also the homeland of peoples that have experienced a difficult colonial past. Much of Canada’s North is still coming to grips with its challenging history and visiting as a Southerner can come with a lot of complicated baggage. We were very grateful for all the opportunities we had to get to know the community of Cambridge Bay. We enjoyed our everyday activities like trips to the shop, staying up to date with current events through the communities’ Facebook page, learning about the history of the area through a visit to the heritage centre, tasting the delicious candied arctic char at Kitikmeot Foods, and even taking part in a drum-dancing session organised for the community’s Elders.

It was difficult to give as much back to the community as we feel we got from it, given the short six weeks that we were there. But thanks to the team at CHARS, we could at least share our project with the community during a talk as part of the public “Polar Speaker Series”. We had the honour of having some of the community’s Elders attend our presentation, which was translated simultaneously into Inuinnaqtun – a very special experience!

Our summer in Cambridge Bay would have not been possible without the support of many people: A big thank you go to the field team Debora Obrist (UZH, SFU) and Erin Cox (POLAR); the whole team at Polar Knowledge Canada / CHARS with special mentions for Nicolas Natel-Frotier, Martin Leger and Calvin Pedersen for the fantastic lab and logistical support; Jesse Jorna (BYU) and Spencer Monckton (Guelph) for good company and helping out in the field; the Swiss support team, including Gabriela Schaepman-Strub, Gilda Varliero, Natalia Dohner and Beat Frey. We also thank the Swiss Polar Institute and University of Zurich for providing funding. Finally, and most importantly a heartfelt thank you to the community of Cambridge Bay – for having us and for letting us conduct the research on their land!

Jakob Assmann is a post-doctoral fellow at the Department of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies & Remote Sensing Laboratories of the University of Zurich in Switzerland. His fieldtrip took place in summer 2023 with financial support of an SPI Exploratory Grant.