ACE terrestrial biodiversity program

Written by Ian Hogg, University of Waikato

Photos: Ian Hogg & Noé Sardet

ACE terrestrial biodiversity program

Written by Ian Hogg, University of Waikato

Photos: Ian Hogg & Noé Sardet

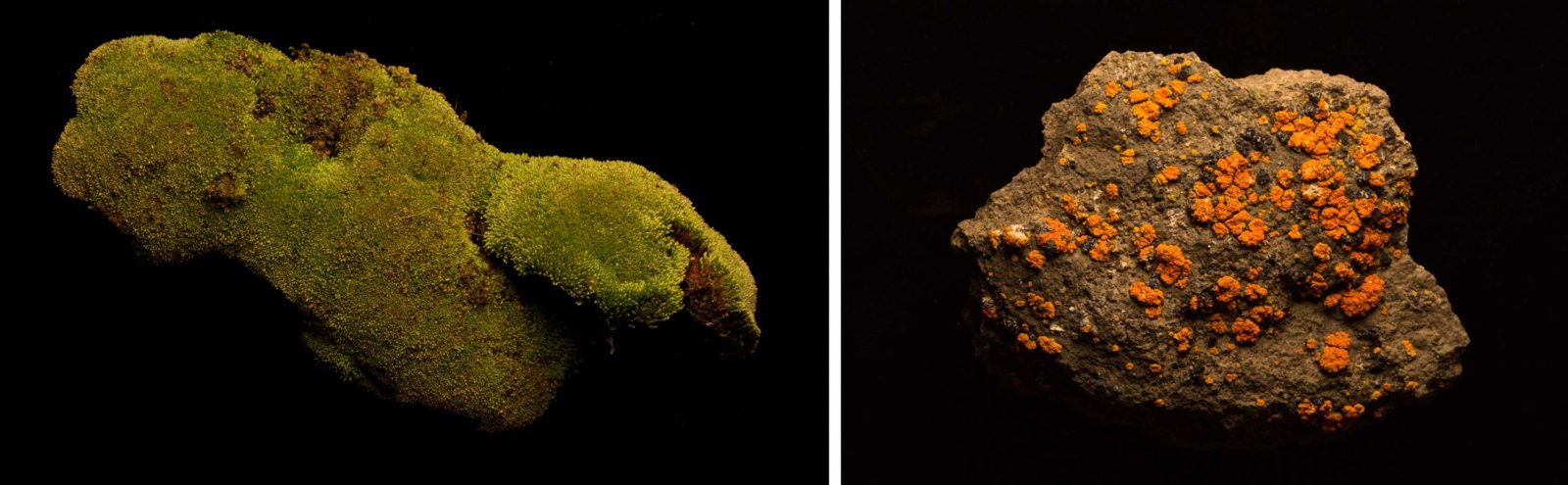

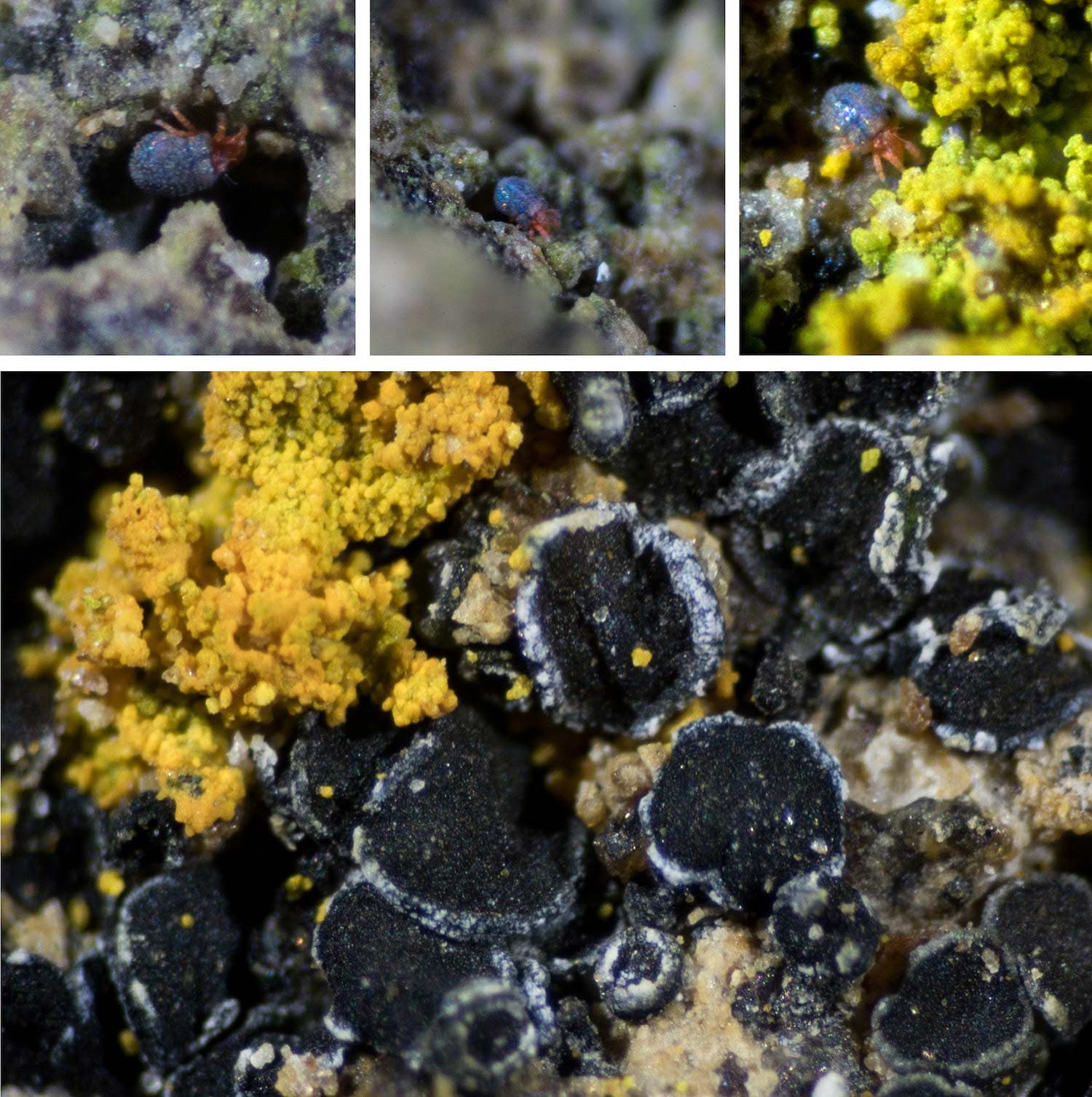

The largest year-round animals to inhabit the Antarctic continent are springtails (primitive insect-like arthropods) and mites – all less than 1.5 mm. The also share the continent with other smaller invertebrate animals including nematode worms and tardigrades (water bears) as well as plants such as lichen and moss. In many cases, these organisms are remnants or relicts from when Antarctica was a much warmer place over 100 million years ago when trees were the dominant vegetation and dinosaurs roamed the land. The landscape has changed much since that earlier time.

Our Project, A Functional Biogeography of Antarctica (AFBA), led by Steven Chown at Monash University is focussed on assessing the terrestrial biodiversity of the Antarctic and sub-Antarctic islands. Our fieldwork includes visiting ice-free area on land and collecting plants such as lichens and mosses and the invertebrate animals such and mites, springtails, nematode worms and tardigrades (water bears). Representatives of moss and lichen samples are collected as well as soil samples for further processing back on-board the ship.

These samples will then be further analysed in our home lab facilities or sent to the relevant international experts for their assessments.

Accessibility of these islands is often a challenge because of high cliffs, sea ice and glaciers. We access these areas via air with helicopter drop offs or by sea with zodiac deployments.

In most cases, we have been collecting new records for each location (e.g. Mt Siple, Peter I) and in some cases these are likely to be previously unknown species. However, of further interest is the connection between locations. Given the terrestrial habitats in Antarctica are highly fragmented, invertebrates have very limited opportunities for contact or dispersal between sites – over time this isolation can give rise to the different species we find at the respective sites. By analysing the DNA of the animals we can tell how related the different populations are as well as how long they have been isolated. In some cases, this can be millions of years.

The information gathered will also help us understand past dispersal pathways for Antarctic terrestrial life as well as how species are likely to respond to an increase in exposed ground due to melting of glaciers and ice caps resulting from climate changes. We can also gain insights into the existence of any invasive species as well as predicting how such species may spread if they were accidentally introduced to Antarctica. In this latter regard, part of our work has involved assisting with the biosecurity aspects of this expedition to ensure that we (and our fellow expeditioners) are not inadvertently transferring plants and animals between sites.