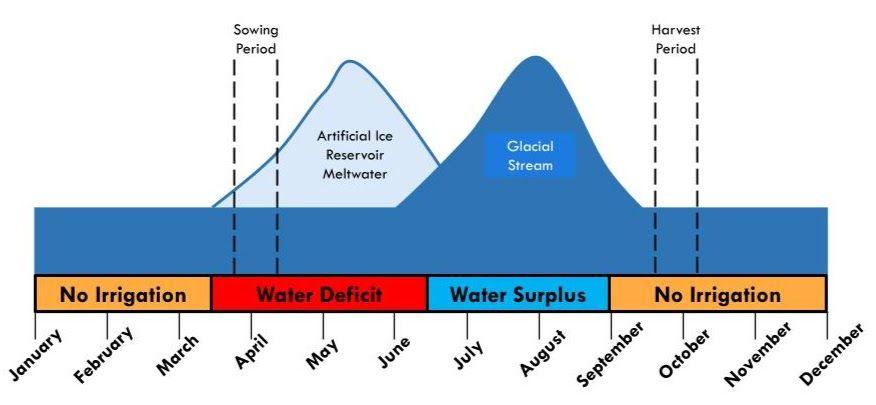

For decades, mountain communities have been watching streams run dry as glaciers upstream retreat. Many have been forced to abandon their ancestral land, but some still remain defiant, proactively trying to halt the decline. In a decades-long struggle, local communities have attempted to engineer glaciers – from calving off ice from ‘parent’ glaciers to building ‘offspring’, to the damming of glacier streams (in the hope that the still water freezes in place) — desperate times have called for radical action. Faced with unprecedented pressure, innovation has continued at pace. Local communities are now growing their own glaciers with nothing but a pipeline and a fountain. They do this with the hope that these ice reservoirs will allow another generation to farm in their ancestral land.

From folklore to science, from religion to technology, these practices of reclaiming glacial water have come a long way. Over the past three winters alone, more than 50 “icestupas”, were built by villages across Ladakh. Despite this rate of adoption, no one really knows whether this technology can be relied upon for climate change adaptation. Our aim, with the Swiss Polar Institute (SPI) grant, was to quantify the potential of this technology by creating the first Ladakh Icestupa dataset that records all the factors responsible for their growth rate.

In Switzerland, our University of Fribourg (UniFR) team had already created several Artificial Ice Reservoirs (AIR). These AIR are those icestupas that have enough weather and water data to run our process-based model. The input dataset, calibration and validation requirements for this model informed the design of the Ladakh Icestupa measurement campaign.

In India, our field partner organisation, Himalayan Institute of Alternatives (HIAL), had already mobilized the Icestupa village teams in a platform called the Ice Stupa Competition (ISC). Through the SPI grant, we wanted to augment the ISC construction campaign with a measurement campaign so that the ISC Icestupas can be turned into AIR. So our team designed and constructed specialized icestupa weather stations that we positioned close to some ISC Icestupas in Ladakh. To calibrate and validate the physical model, we needed independent observations of ice volume and temperature. So we appointed field staff who took thermal images and performed drone flights twice every month. As we were unsure about the data quality of our icestupa weather stations, we also installed two Campbell weather stations (sponsored by National Geographic) and also temporarily brought the weather station previously used to measure the Swiss AIR to Ladakh. We were also able to conduct the first of its kind ground penetrating radar (GPR) survey of the AIR. This survey is expected to provide ice volume estimates with even higher precision compared to our drone surveys.

We ended up transforming Icestupas of 3 ISC villages into AIR. One of these villages, called Kullum, was abandoned recently as the spring water supply was no longer sufficient for farming. Some villagers of Kullum still regularly visit their now empty houses to keep the prayer lamps alight. They had enrolled in the ISC this winter with the hope that at least some of their farmlands can eventually be put to use. As Kullum was far away from the city of Leh, we spent a couple of nights in one of these abandoned households. It was moving to realise what was at stake for these villagers first-hand. All throughout our work in Kullum, we were in disbelief that such a beautiful village is left uninhabited because of lack of water.

The impact of the pandemic on our fieldwork has been difficult to forget. The SPI fieldwork was originally planned for a duration of two months and with a team of three people. The pandemic stretched the fieldwork to five months and made the person responsible for constructing the raspberry pi weather station only remotely available. Moreover, we had several periods of blackouts due to people in the field team contracting the virus. Financially, we suffered significant losses due to delays in our weather station transit due to quarantine requirements in the customs office. Even as I write this, we are praying for the complete recovery of one of our field staff from Covid.

We also learned a lot from being able to deploy the sensors in such a remote environment. The icestupa weather station was built from scratch from a raspberry pi and specialized sensors (sponsored by DFRobot). Together with the field staff, this was assembled and deployed in Ladakh. Each of these weather station kits cost us just a fraction of the cost of our Campbell weather station. As a consequence, we now have trained field staff who can deploy such weather stations independently, in a region where open-source weather data is non-existent.

Now, with the successful acquisition of the AIR dataset, we hope to quantify the potential of these ice reservoirs not just in Ladakh but for any community worldwide who want to put their winter to use!

Suryanarayanan Balasubramanian is a PhD student in the Alpine Cryosphere and Geomorphology Group, at the University of Fribourg. His field trip started in August 2020 and went on for a couple of months, with financial support from a Polar Access Fund grant.

Header drawing: © 2021 Suryanarayanan Balasubramanian, all rights reserved

© 2021 Suryanarayanan Balasubramanian, all rights reserved