Project goals and background

In 2024, I had the opportunity to launch a research project in East Greenland, supported by an SPI Exploratory Grant, to investigate the spatial distribution of bacterial diversity across interconnected compartments of an Arctic lake. Lakes are complex ecosystems that host diverse microbial communities, with aerosols, water, and sediments each serving as distinct habitats supporting unique bacterial populations. These habitats offer valuable perspectives on microbial dynamics across spatial and temporal scales. Bacteria are the most abundant life forms in cold lakes, where they play vital roles such as degrading organic matter and contributing to primary production, making them fundamental to the structure and functioning of the trophic chain. Arctic lakes are highly dynamic systems subjected to extreme environmental conditions – including prolonged ice cover for much of the year, intense winds, and heavy snowfall.

Existing research has typically focused on microbial dynamics within the water column or sediments, yet Arctic lakes are physically connected to surrounding compartments such as the ice cover, snow during wintertime, watershed soils, and the atmosphere – each potentially hosting distinct bacterial communities. These interconnected environments thus likely support microbial transport fluxes and perform crucial ecological functions that remain poorly understood. Aerosols, originating from surface water, disperse through the air and are influenced by rapidly changing environmental factors like wind and humidity. In contrast, microbial communities within the water column respond to slower-changing parameters such as temperature and nutrient availability. Sediments accumulate bacteria and organic matter over time, acting as natural archives that reveal past environmental conditions and microbial populations. Despite their interconnectedness, studies often treat aerosols, water, and sediments as separate compartments, missing opportunities for comparative insights.

The aim of this project was to shed light on bacterial diversity across these diverse connected lake compartments and to advance our understanding of potential microbial fluxes at the interfaces of air, ice, water, and sediments. To achieve this, I conducted two field expeditions – in June and September – to collect samples of bioaerosols, lake water, ice, and sediment cores from a remote Arctic lake in East Greenland. These sampling periods, immediately following the Arctic winter and summer respectively, were designed to capture microbial community dynamics under sharply contrasting environmental conditions. The campaigns were particularly challenging due to the remoteness of the lake, situated within a known polar bear area, as well as the harsh Arctic weather and logistical constraints imposed by the upcoming polar night in September. These are my fieldnotes – I hope you enjoy reading them!

Left: Collecting bioaerosols using a Niosh aerosol cyclone collector against very strong Arctic winds during the start of a storm in June 2024. Right: Sampling of ice cover from “Dolphin Lake”. © Anna Carratalà, all rights reserved

Why East Greenland?

The geographical location for the expeditions was selected based on data I collected during a previous field campaign in 2023, during which I identified hotspots of bacterial diversity along a latitudinal gradient in East Greenland. These findings guided the selection of a high-priority region near Constable Point, where bacterial richness appeared to be particularly elevated. Logistical considerations also played a key role in site selection. Constable Point hosts a small international airport, offering relatively reliable access to diverse remote lakes. Candidate lakes within the identified diversity hotspot were initially chosen using satellite imagery, based on apparent accessibility, suitable size and sufficient depth.

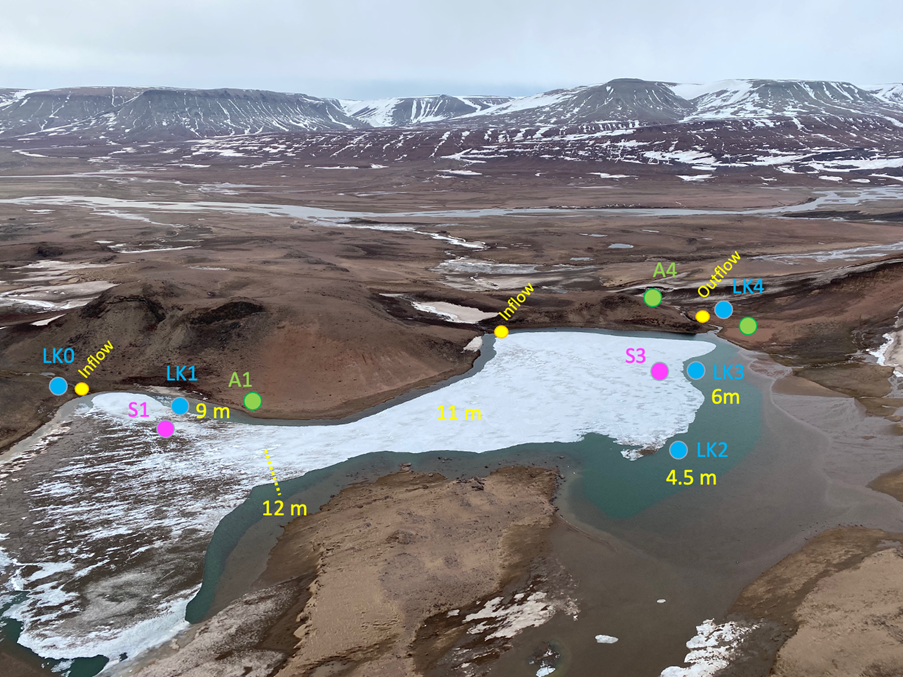

During the first expedition in June, we visited two of the lakes by helicopter for an on-site evaluation. The final study site – located approximately 30 km from the Constable Point airport and far from any human settlements – was selected for its environmental suitability and logistical feasibility. For working purposes, the lake was named “Dolphin Lake”, owing to its shape which loosely resembles a dolphin when viewed from the air. The surrounding area provided a safe and stable location to establish a campsite, which served as our base for both expeditions. Due to the lake’s remoteness, the camp was entirely unsupported, requiring us to be fully self-sufficient for the duration of our stays. All necessary equipment, food, and scientific materials had to be transported by helicopter and carefully planned.

Once in the field, we had no access to resupply or external assistance, which demanded meticulous preparation. To keep fieldwork costs to a minimum – especially in such a remote and logistically demanding environment – the expedition team was limited to only two participants: myself and Henrik Lassen. A former member of the Danish Sledge Patrol and an expert in East Greenland field operations, he provided logistics and polar bear safety support during the sampling.

June 2024

The sampling campaign we conducted in June was significantly challenged by strong winds and snowfall, that began only a day after our arrival and forced us to remain confined in the sleeping bags in our tents for two days, waiting in isolation for weather conditions to improve before we could resume fieldwork. This offered us a unique opportunity to spend long hours reading and meditating, attentively listening to the sounds outside while fully experiencing the raw and unforgiving nature of the Arctic. The temperature was not that low, around 2°C according to our meteorological station, but the wind was very strong and for sure freezing so we could not spend too long outdoors without starting to feel the cold sinking in our bones. On occasions the wind gulfs were so strong that would bend the tent sideward and squeeze me under.

Once the weather improved a little bit, we resumed the sampling targeting water, ice and aerosols as planned. We used a small inflatable boat for the water samples. We tied it to the shore for safety and sampled bioaerosols using a Niosh cyclone collector for three hours to ensure that we would capture sufficient particles for the downstream analysis in the lab. We collected samples in diverse sites and depths of the lake to examine spatial differences in microbial patterns – close to the inflow, in the deepest part of the lake and close to the outflow.

Another aspect of this campaign to highlight that was the trip took place during the midnight summer, which granted us long sunlight hours to conduct work during the whole day as needed. We installed a little lab in the tent, for water filtration and preparation using a generator, so we could conduct “lab work” every day after collecting the samples.

September 2024

In September, we returned to “Dolphin Lake,” following the same logistical strategy as in June. We chartered an Air Greenland helicopter to reach the site, transporting all the equipment and supplies needed to work independently in the field for 15 days. The main challenge during the autumn expedition was the rapidly shortening days and the heightened risk posed by polar bears – especially at night, when our ability to see them in advance and react would be a bit limited. To address this safety concern, we brought a thermal night camera and rented a sledge dog from a local owner. The dog, that we named Hyena, always stayed close to us and served both as a companion and an early warning system, trained to bark if a bear approached the campsite.

In autumn, the lake remained ice-free, which made access to the water surface easier than in spring. This allowed us to carry out additional sampling activities under more stable conditions. One of our key objectives for this expedition was to collect sediment cores. To achieve this, we brought an inflatable boat and used a gravity corer to extract samples from two sites within the lake. Lake sediments act as natural archives, gradually accumulating particles that settle from the water column over time. These layers capture not only organic and mineral material but also microbial DNA, preserving a chronological record of past bacterial communities and environmental conditions. By analysing these sediment cores and applying radiometric dating techniques, we can reconstruct temporal patterns in bacterial diversity, compare them with current community structures, and gain insights into how microbial ecosystems have responded to past and present environmental changes.

As the polar winter approached and the nights grew longer, the task of standing night guard for polar bear safety was often rewarded by the magical display of northern lights, dancing across the sky and reflecting on the still, dark waters of the lake.

The first results

I am currently continuing laboratory analyses to characterise the microbiome across the extensive set of samples collected during the two field campaigns. Preliminary results have revealed significant bacterial abundance within the various lake compartments, including bioaerosols. Using 16S rRNA qPCR, we observed that bacterial abundance increased during the Arctic storm in June and were notably higher in ice cover samples compared to the water column. This pattern suggests that atmospheric deposition through rain and snowfall may contribute substantially to bacterial biomass accumulation in the ice cover during winter. Additionally, we detected elevated ammonia concentrations in the ice relative to the water, indicating a possible enrichment of microorganisms involved in nitrogen metabolism. Ongoing analyses will help clarify the bacterial fluxes between these interconnected compartments. Furthermore, dating of the lake sediment cores indicates an estimated age of around 300 years. I eagerly await sequencing results from the sediment, ice, and water samples to deepen our understanding of how bacterial communities in this lake have evolved in response to both past and present environmental changes.

Left: Hyena, the dog we rented for polar bear warning in September. Right: The Air Greenland helicopter that came to pick us up after the fieldwork. © Anna Carratalà, all rights reserved

Final thoughts and remarks

To conclude these fieldnotes, I would like to express my gratitude to the Swiss Polar Institute for their support of this project, as well as to Henrik Lassen for his impeccable assistance and dedication in the field. Working in the remote “Dolphin Lake” offered invaluable lessons about the complexities of Arctic logistics and the challenges posed by the unpredictable harsh climate. This experience not only deepened my appreciation for the resilience required to conduct research in such extreme environments but also significantly enhanced my skills as an expedition leader. I am grateful for the opportunity to contribute to our understanding of these fragile ecosystems and look forward to sharing more insights as the project progresses.

Left: Filtering lake water under the Arctic sun and a shot of the northern lights visiting us almost every night in September. Right: Sediment core collected in September dating up to 370 years ago. Sequencing will reveal the composition of bacteria communities of diverse time periods and the corresponding environmental conditions. © Anna Carratalà, all rights reserved

Anna Carratalà is an Environmental Microbiologist at the Laboratory of Environmental Virology at the EPFL in Lausanne, Switzerland. Her fieldtrip took place in summer 2024 with financial support of an SPI Exploratory Grant.