As part of our art and science collaboration in the context of the PolARTS programme from Swiss Polar Institute and Pro Helvetia, we (Pauline Agustoni and David Janssen) had the chance to travel to Southern Greenland for a three-week field trip from 24 June until 15 July 2025.

For a year and a half, we have been working as an art and science duo operating between geochemistry and design. With our experimental project Hydrorecord, we explore ways of understanding and expressing lake research on a multidisciplinary level.

We travelled as part of a bigger scientific field trip organised by Eawag (Swiss Federal Institute for Aquatic Science and Technology) group leader Blake Matthews. The overarching scientific aims of the fieldwork were to assess impacts of species distribution on lake ecology and biogeochemistry. South Greenland serves as an ideal location for these investigations due to the minimal anthropogenic impacts, large number of small lakes which can serve as natural replicates, clear impacts of climate change and connectivity, and the relatively simple potential lake categories in terms of general food web structures.

Our first research location was Isortoq, an area in Southern Greenland where several lakes of interest are located. Accompanied by Blake Matthews, Danina Schmidt and Marek Svitok, we focused on the study of several lakes of glacial origin, and with different histories of connectivity to the glaciers still present. Because the glacier is still adjacent to the lakes we visited, including new lakes formed in the last decades during glacial retreat (see satellite images below), the Isortoq field site represented the more dynamic side of our field trip – the recent impact of glacial processes was visible on a daily basis.

Satellite images of glacial origin lakes we visited during our Isortoq field trip. The image on the left is from 2025, while the image on the right is from 2012. The rapid glacial retreat dramatically changed lake characteristics through loss of connectivity over this time, and new lakes have been exposed from under the retreating ice.

Our activities focused on the sampling of nearby lakes, some of which had direct glacial influence in the last decades and some which did not. Our interdisciplinary team worked on several aspects of the limnology, covering water chemistry and physical parameters (temperature, transparency, pH, nutrient and carbon concentrations) and a wide range of samples covering the aquatic ecosystem (fish, zooplankton, phytoplankton, benthic invertebrates), along with the artistic sampling and recordings. A total of 25 lakes were researched and sampled, with a range of specific tools used (inflatable kayaks to access the lakes, deployable sensors, handheld or deployed nets, small fish traps, sediment collectors, handheld water scooping and tube sampling, video, audio and still image recording, sculpture installations, contact prints). A key aspect of the collaboration included mounting recording devices onto the scientific sampling equipment, so that material could be collected for both the scientific and artistic aspects of the project.

These weeks in the field represented a unique opportunity to get familiar with the processes behind the science for Pauline, as well as a great chance to understand the artistic approach for the science team – the time spent together was a very intense learning moment with true exchange happening between the people in the group. We were actively involved in each other’s research, helping each other out during our activities, be they scientific or artistic. During our hikes to the lakes, we would discuss many topics, ranging from questions about how we work, the analysis of a local plant, reflections about the art field, parallels between grant applications in art and science, to personal life stories. The evenings also gave the science team a chance to have a glimpse of Pauline’s previous projects and learn more about aspects of her practice in general, which enriched the collaborative activities throughout the working days. These moments, happening on the side of the sampling, represented precious moments of exchange. All team members were highly curious and interested, and we have great memories of the exchange that happened during the field trip.

As for the art and science collaboration, it was very active in Isortoq. We spent the first two weeks of the field trip exploring different techniques and means of expression.

Fascinated by the technologies behind our understanding of nature, a big part of the art and science component focused on exploring tools and processes of both science and art. These technologies provide us with information about natural processes that we cannot understand through direct perception alone. They are a sort of bridge between us and what is researched. Similarly, a video or photo camera captures moments of which our visual memory keeps only a vague impression. Moreover, the images produced by the artistic component of the research are editable, allowing further understanding of natural processes through visualisations.

A thorough photographic documentation of scientific and artistic tools was carried out. In an almost matter-of-fact way, the documentation reveals the (sometimes overlooked) objects behind the science and the art.

Solar paper imprints of the various tools we used during the field trip were made in a series that blurs the frontier between scientific and artistic devices. Between x-rays and ghost imagery, the series conveys the idea of an imaginative set of tools which are ambiguous.

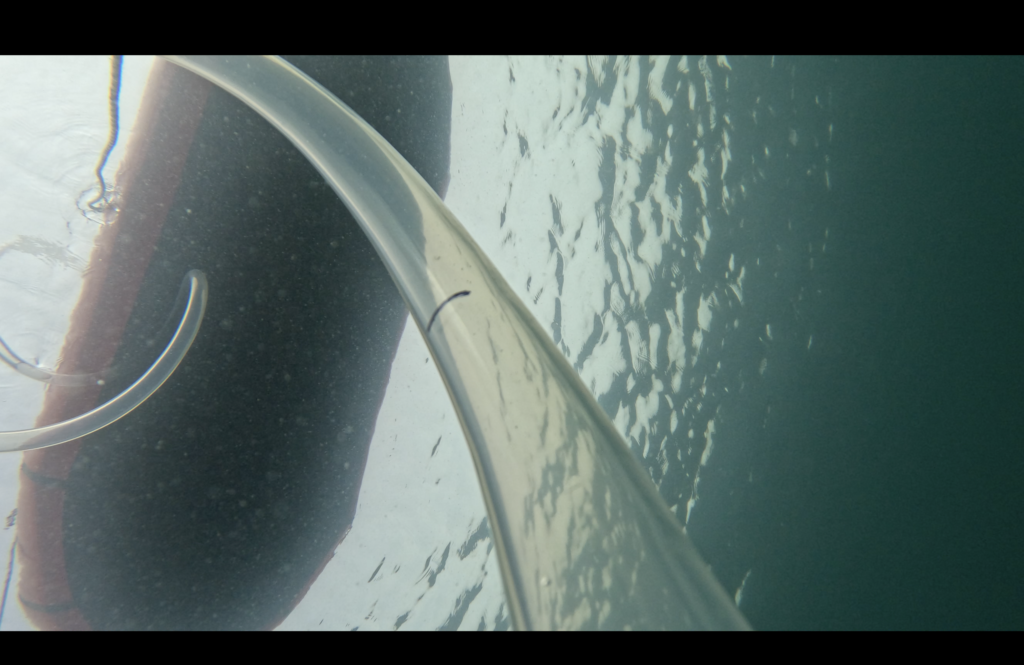

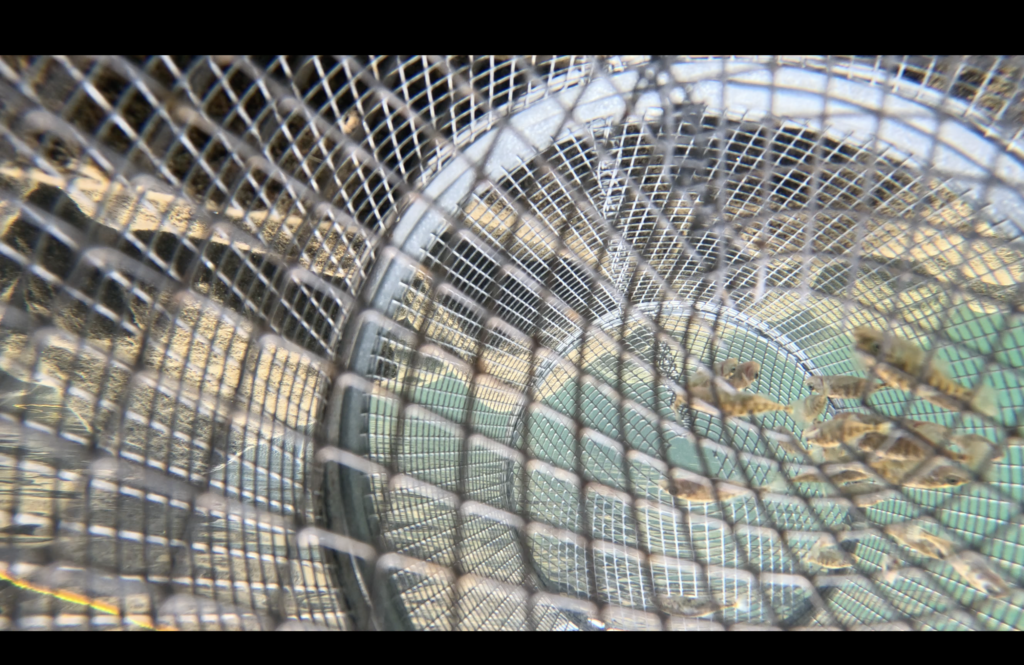

One of our most successful experiments in researching the art and science tools was to enhance existing scientific devices with add-on cameras to capture the scientific process from the perspective of a given tool. We were surprised to see how well the movements are conveyed when the camera records the tool being handled. One gets an idea of the gestures behind the science, as well as the resistance of the investigated elements: water, rocks, landscape. It communicates something about the physicality of fieldwork through moving visuals. The true nature of the scientific actions is often lost in scientific presentations of the results, where relatively dry and direct factual statements such as “Water samples were collected by inflatable kayak…”, or “Benthic invertebrate samples were collected with a kick net in the littoral region…” fail to capture the process.

© Pauline Agustoni, all rights reserved

Some of the videos, especially the ones where working hands are not visible, give the impression of a total change of perspective. Seeing the research happening from the point of view of the tools produced beautiful shots, abstract yet in a way that achieves a closer proximity with the researched element.

Underwater video stills

A metal installation was designed prior to the trip in order to explore the concept of balance. Water pouches from various lakes were added to the installation, making it shift weight from one to the other side.

© 2025 Pauline Agustoni, all rights reserved

In general, these activities were experimentations in the ways we see and understand. Being part of a scientific group in the field enhanced in many ways the artistic research, which highly benefitted from being well informed by expert scientists about the invisible processes behind the lake’s environments. Seeing the world from the scientists’ perspective allowed a deeper understanding and appreciation of the magic and beauty behind the natural processes that shape a landscape, along with new knowledge on where and how to look to read its cues.

A series of photos unveiled the poetry of a scientific process by showing the aesthetics of fish trap ropes in water.

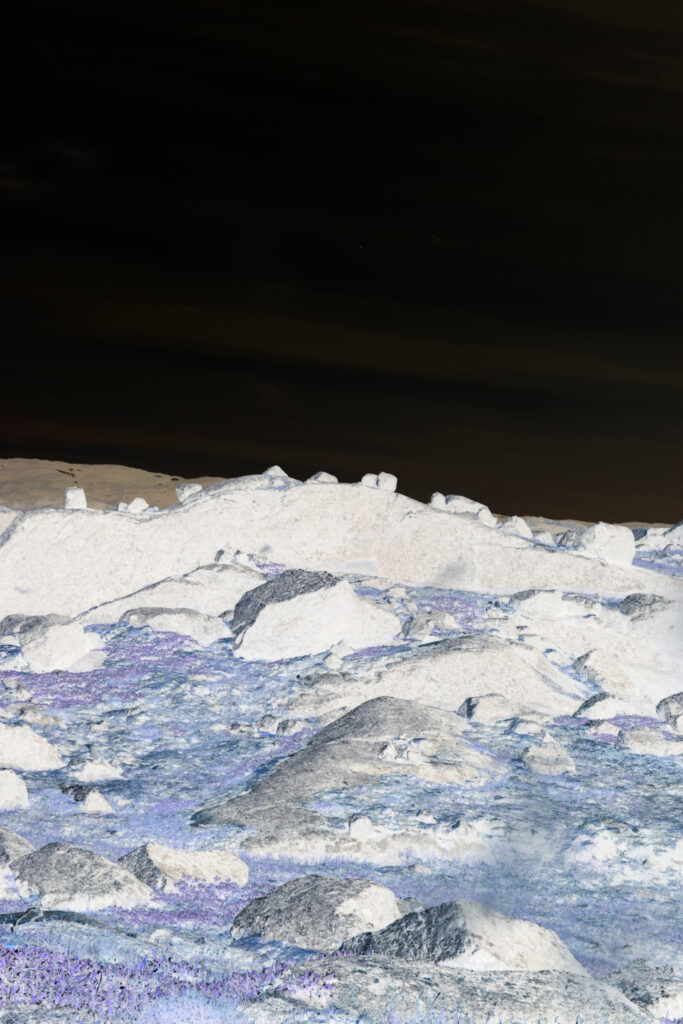

A series of positive and negative images of erratic boulders focuses on the beautiful placement of erratic boulders by the retreating ice sheet in the landscape.

In addition to the sampling component in Isortoq, Pauline travelled to Narsaq for a few days to stay at Narsaq International Research Station, a space open to scientists and artists working in Southern Greenland. Thanks to the help of the station’s team members Lise Autogena, Ivalo Motzfeldt, Nivi Stidsen and Ane Marie Poulsen, she hosted a workshop for children at the local youth club, Klub Qaqqavaarsuk. Making use of a mix of scientific devices, toys and gathered plants, the children created collaborative compositions on solar reactive paper. While being very hands-on, the workshop also introduced the young participants to the scientific objects used in the context of lake research.

The workshop was part of our wish to connect with locals as well as give something back from the research to the community. Beside sharing research data with Greenland, guides about conducting ethical research in Greenland emphasize the importance for science groups to also engage in knowledge transfer and public presentations.

Impressions of the workshop in Narsaq

Having the chance to work in-depth on the topics that stemmed from the start of our common project enhanced our belief that they are essential and relevant to talk about. In both the scientific and artistic fields, we talk more about the produced research than about the tools and devices that allow and directly influence the work. What are the tools and devices behind limnology and art? How does tool design directly influence the type of research that is done with them? What can/can’t they do? What would a hybrid artistic/scientific device look like? What type of data would we like it to record? Experimenting with these questions in the field allowed us to test a manifold of ideas and reflect on a deeper level, which brought us many new inputs and inspirations.

The fact that we could join a larger group and collaborate with other scientists also added to our learning experience. Being part of a larger research trip enhanced what we learned, as we could learn immensely from the other scientists, as well as share our knowledge and practice with the group.

The field trip represented a key moment of our collaboration. Working in close proximity, we had an accelerated and intense collaboration. We are extremely thankful for the chance to have had this field trip, and fully realize how essential it has been in the larger context of our PolARTS collaboration.

We would like to warmly thank Swiss Polar Institute, Pro Helvetia and Eawag for their support with our project. Our special thanks go to our fieldwork companions Blake Matthews, Danina Schmidt, Marek Svitok, Adam Janto, Jordan Martin, Angelina Arquint and Milan Novikmec, as well as our hosts in Isortoq Freyja Stefansdottir and Stefan Magnusson.

Pauline Agustoni (designer and artist) and David Janssen (research group leader at Eawag – Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science & Technology, Aquatic Geochemistry) are beneficiaries of the PolARTS funding scheme, a joint initiative of the Swiss Arts Council Pro Helvetia and the Swiss Polar Institute. Their fieldtrip took place in summer 2025 in the context of their project ‘Hydrorecord: Water as a connector across space and time’.