Having grown up surrounded by northern peatlands (wet ecosystems that accumulate peat), I greatly respect these unique ecosystems. In old Finnish folklore, peatlands are often depicted as something ominous, mysterious, and dangerous: the dead could be seen guarding their hidden treasures in the ancient peat, diseases could spread from their depths, and the “eye” of the peatland was a gate to the world of the dead. Despite these scary stories and the occasional fear of falling into the “eye”, my interest in peatlands grew over the years, and a couple of weeks ago, I found myself doing something that the 13-year-old me would be very proud of: taking peat samples from a permafrost peatland.

In my PhD, I investigate the various effects plants can have on wetland (ecosystems with the water table near or at the ground surface; peatland is a type of wetland) methane emissions. Methane is a strong greenhouse gas mainly produced in soil conditions with low oxygen availability, which can be caused by high soil water saturation. Because of this, wetlands are considered the largest natural source of methane globally. However, wetlands are still keeping their secrets tightly in their depths, as we still don’t fully understand how exactly the complex network of different living organisms, such as plants and microbes, and non-living factors, such as water and soil temperature, functions as a whole. One of the keys to shedding light on the mystery of methane production in wetlands is to investigate the role of plants, and especially their roots, in wetland methane cycling.

To understand how different plant root characteristics (traits) influence wetland methane processes, I set out to Stordalen palsa peatland in Abisko, northern Sweden, a famous site among researchers. Palsa peatlands are typically located in the discontinuous permafrost zone, where peat mounds with permafrost cores ( i.e. palsas) form in cold climate conditions. However, climate warming has led to permafrost thaw and the subsequent disappearance of these unique peatland forms. With permafrost thaw, soil water content and vegetation composition can change remarkably from dry shrub-dominated palsas to wet fens dominated by cotton grasses (Eriophorum) and horsetails (Equisetum). Due to these changes, it is not hard to imagine that there might be alterations to methane cycling as well.

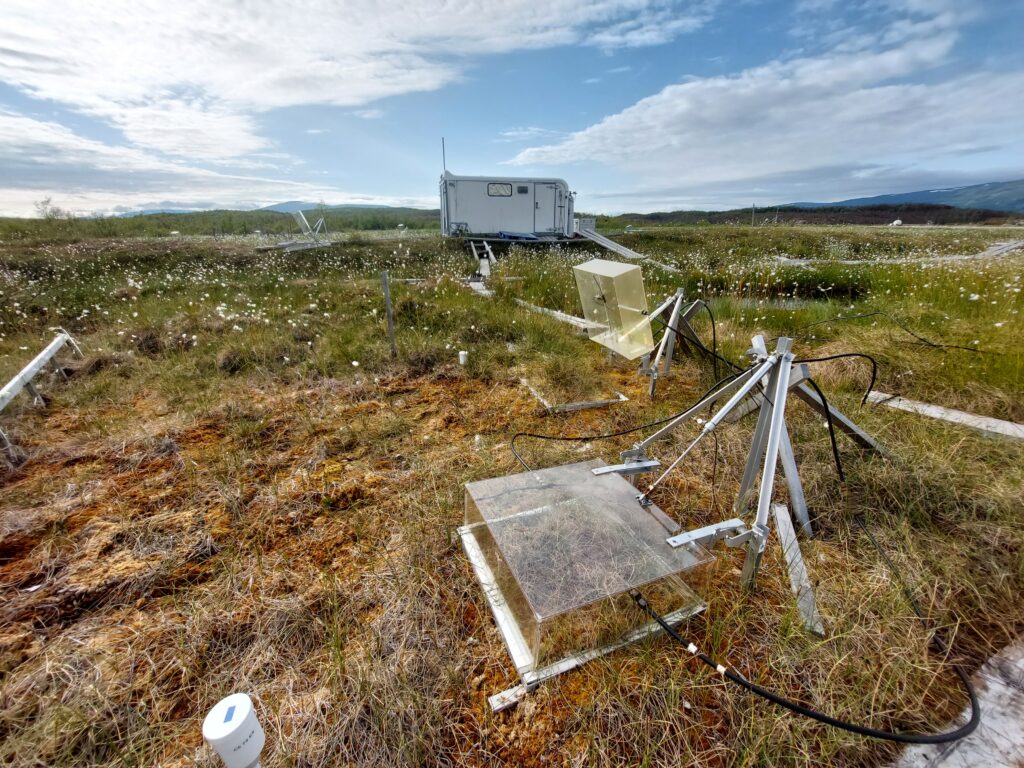

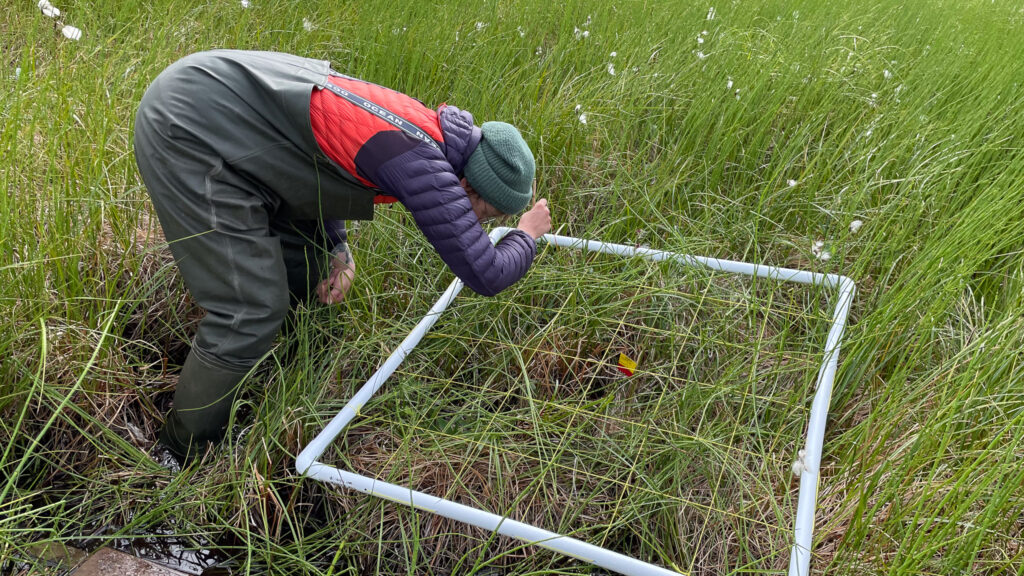

Permafrost thaw is (unfortunately) also present in the Stordalen mire with a gradient of intact palsas, partly thawed bogs, and completely thawed fens. From a researcher’s point of view, it provides an excellent environmental gradient to study the effects of plants and their roots on methane cycling in a changing environment. To start our investigations, my assistant and I conducted vegetation surveys to analyse the vegetation composition at the methane measurement plots. In Stordalen, methane is measured with automatic chambers (point measurements) and an eddy covariance tower (ecosystem-scale measurements). In this project, I only focus on the chamber measurements.

After assessing the vegetation at the chamber plots, we moved on to our sampling plots, where we conducted the same vegetation surveys and dug into the secrets of the ancient peatland by taking peat core samples. The coring was by far our favourite moment of the field trip! Seeing the layers of time in our hands was an amazing feeling.

Even though the schedule was rather tight, we enjoyed the beauty of Stordalen every day and managed to avoid stepping into the legendary “eye”. Being able to go on this trip was all thanks to the Swiss Polar Institute, who granted me the funding to conduct the field research. The next steps will include picking out roots from these precious core samples and analysing them for various root traits that will hopefully help us shed more light on the hidden methane cycles of the thawing peatlands.

Tiia Määttä is a PhD candidate at the Department of Geography, University of Zürich. Her fieldtrip took place in summer 2023 with financial support from a Polar Access Fund grant.